This is the first in a series of articles about reforming our healthcare system. If you are interested in attending one of our upcoming virtual panel discussions related to this new series, please register here.

Canada’s provincial healthcare systems are in in a mess, getting more expensive all the time while services delivery declines. For at least the past decade, we have been coping with rising populations, especially aging populations; declining financial and human capital; and, of course, a global pandemic. To counter these headwinds, the provinces have increased funding and received greater health transfer payments from the federal government. Yet with all this spending, citizens are getting fewer medical services from the system. With healthcare being such a core part of our society, the government needs to turn its focus on more productive programs, not just more spending.

A recent study undertaken by the OurCare group in Ontario found that residents would like the province to move away from the traditional fee-for-service model for primary care, to a place where all residents have access to an integrated care team (with Ontario’s Family Health Teams being one example). While this type of model provides superior care, moving the entire system to that model would significantly increase costs and demands on a system that is already stretched to the limit.

More money does not equal more service.

Healthcare funding has been increasing at unsustainable rates for a long time, and governments cannot continue to increase healthcare spending without impacting other critical programs. From FY2012 to FY2020, Ontario’s Ministry of Health spending grew at a 3.8% CAGR compared to the 2.8% rate of Ontario’s inflation and population growth combined. But despite increased spending, the output from physicians (as measured by the annual services performed) and the services per 100,000 Ontarians actually decreased.* In fact, using data from the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) for that period, while the number of physicians increased by 23%, the annual number of services decreased by 18%.

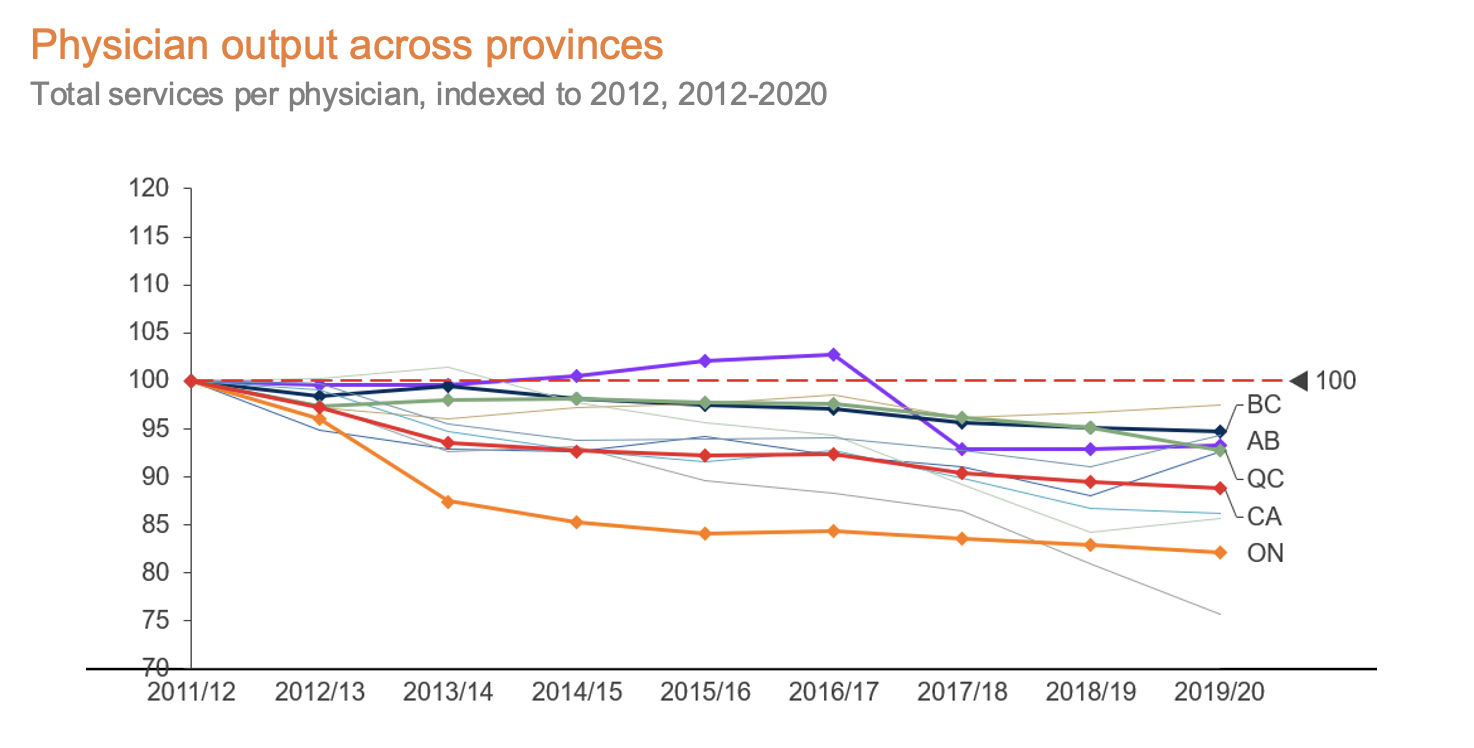

Ontario is not alone in this trend, but our healthcare system’s productivity is declining more rapidly than that of other large provinces.**

*We are excluding FY2021 to avoid the adverse impacts of COVID.

**All provinces included but only provinces with populations more than four million people highlighted.

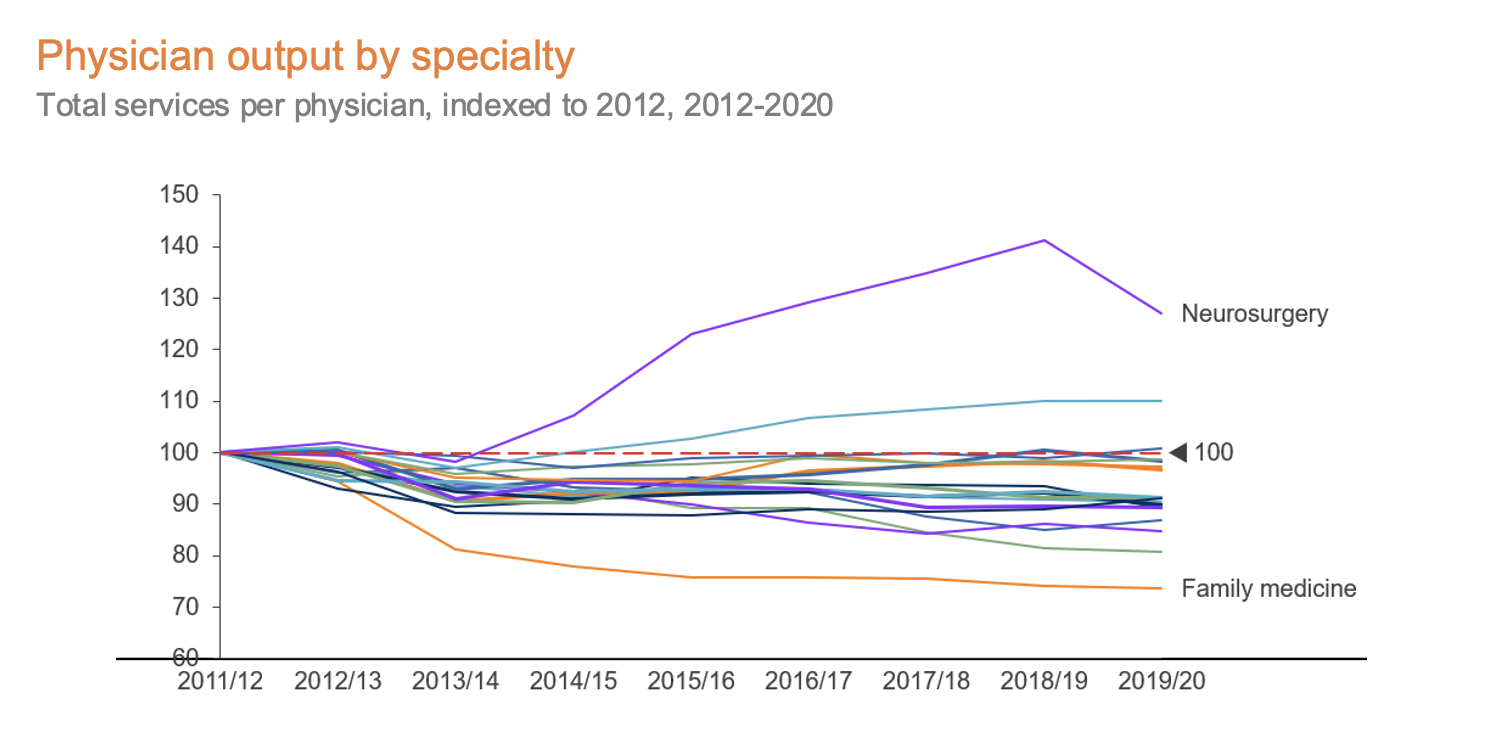

In Ontario, services declined in almost all specialties (exceptions include neurosurgery, ophthalmology and thoracic/cardiovascular surgery). This decline is led by the most far-reaching of the specialties, family medicine; with per physician services declining 26%, it is one of only two specialties in Ontario where the total number of services also declined, with ~5.2m fewer services performed in FY2020 vs. FY2012. While fewer services could be associated with better health outcomes, the evidence points to the contrary. We are seeing longer wait times across the board, especially for specialists; Canadians are living with issues for longer and likely aren’t seeing improved health outcomes.

There are many reasons for the declining output across the board, some of which have been widely discussed, such as:

- Increased workloads for charting, referrals, and follow-ups;

- New tools like electronic medical records (EMRs) creating a larger time burden than traditional paper charts;

- Increases in complex cases demanding more of a physician’s time per patient; and

- Increased demand and expectations from patients for tests and referrals.

The above examples are part of what is behind the well-documented physician burnout we are seeing in Ontario – burnout which leads to physicians spending less time seeing patients, with many reducing their clinic hours or shifting to delivering care in private settings.

The solution that is most often discussed is hiring more clinicians, but continually increasing capacity is not an option. We need to look at the other side of the equation: reducing the demands on the system to allow clinicians to focus on the highest-needs patients. While there are many ways to reduce the demand, we believe there are three evidence-based solutions that have demonstrated success in other geographies and deserve increased attention.

1. Increased emphasis on home-based care

There is plenty of evidence to support the value of home care services, both from an outcomes and patient satisfaction perspective, and also from a cost of care perspective. And yet the availability of home-based care in Ontario is inadequate at best. By increasing the availability of home care options for members of our society, we can help reduce avoidable hospital visits. There are a number of promising private companies delivering these services; with the appropriate funding and regulatory oversight, they can be scaled up much more quickly than the clinician workforce, helping to alleviate some of the pressures on our system.

2. Greater deployment of alternative care options

COVID has seen massive changes in healthcare delivery models, particularly by accelerating the adoption of virtual care visits. Although OHIP’s concerns about abuses in the program have reduced the availability of virtual care, the system does allow for more efficient use of physician time and a more convenient interaction for patients. In addition, although the jury is still out on the effectiveness of solutions such as pharmacist prescribing, methods of reducing the burdens on clinicians should continue to be explored and tested. Our government should be working with these alternative options to ensure tight integration into the existing healthcare system so that we don’t end up in a situation with more disconnected care than we have today.

3. Programs focused on keeping seniors healthier for longer

It is no surprise that seniors place the greatest demand on our healthcare system; in 2020, individuals 65 and older accounted for 44% of healthcare expenditure, but only 18% of the population (CIHI 2022). And with the aging of the population in North America, the demands of this segment on both capacity and healthcare expenditure will continue to increase. There are many different models of care and social programs spreading across the US and other regions that specifically target this population to slow the decline in health status, improving the lives of seniors and decreasing the demands on providers. Our government should be working with innovators in the space and developing new funding tools that incentivize and help seniors maintain their health to avoid unnecessary ER and doctors’ visits and the consequent demands on our system.

These are just some approaches that can help alleviate pressures on our healthcare system in the near to mid-term; they will not be easy to implement, and they will necessitate changes in funding models, practice models and behaviours from clinicians, the government, and, most importantly, residents. We invite you to join us over the next few months as we explore these and other ideas with both near-term and long-term benefits.